Free Shipping! - Order $99 or More (excludes framed items)

The Artist

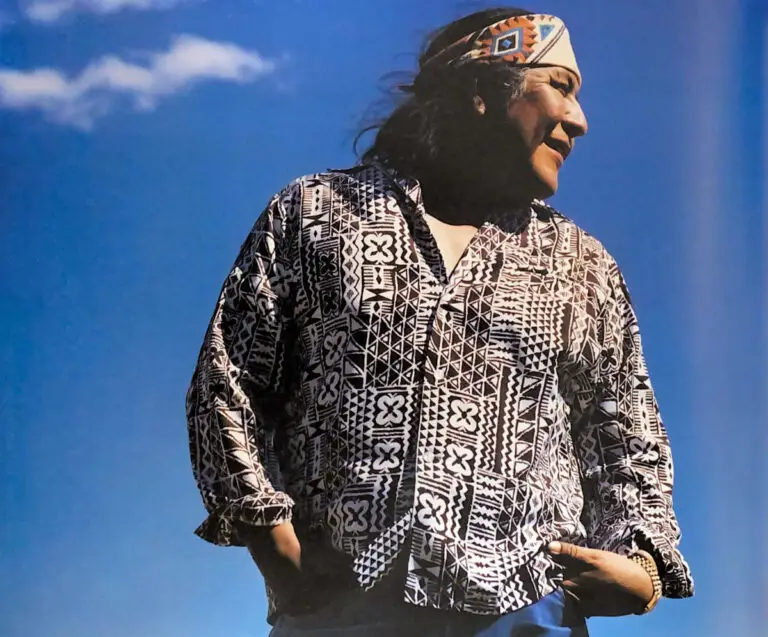

“I was born near Canyon de Chelly in Chinle, Arizona July 26, 1931. I spent my early years living close to nature and Navajo tradition. My family was rich in artistic talent and creative spirit, but not in material possessions.

I have been fortunate to live and work in the beautiful Taos Valley, of New Mexico, an environment also rich in artistry and tradition. The spirit of Taos has encouraged and inspired me, and my focus as an artist matured here.

I’m truly grateful to my friends, drinking buddies, family, patrons, and my loyal staff—all of whom have made my way of life here possible. Thanks for sharing the light.” – R.C. Gorman in 1998

“I was born near Canyon de Chelly in Chinle, Arizona July 26, 1931. I spent my early years living close to nature and Navajo tradition. My family was rich in artistic talent and creative spirit, but not in material possessions.

I have been fortunate to live and work in the beautiful Taos Valley, of New Mexico, an environment also rich in artistry and tradition. The spirit of Taos has encouraged and inspired me, and my focus as an artist matured here.

I’m truly grateful to my friends, drinking buddies, family, patrons, and my loyal staff—all of whom have made my way of life here possible. Thanks for sharing the light.” – R.C. Gorman in 1998

Years in Taos

The Taos Diaries 1968-1998 from the book by Virginia Dooley, Navajo Gallery Director

I began keeping Gorman’s diaries in 1972. They were started at the suggestion of his tax advisor as a way to keep a record of his travel and entertainment expenses. The diaries also helped keep his charge cards in order—I can tell you where he had lunch on July 3, 1975; it was at La Doña Luz.

As my years with R.C. progressed, these journals developed into a chronicle of his career, how it was started, and how it kept on track. His exhibits, honors, interviews, and international tours were all detailed.

The focus of this catalogue, however, is to highlight the Gorman bronzes. The incidents described in the narrative, therefore, are meant as vignettes of his life in Taos over a period of thirty years. It is hardly the complete story. But, like Gertrude Stein, who wrote the autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, I can’t wait to start on the Gorman Memoirs.

Prelude

Before moving to Taos, R.C. Gorman had enjoyed an active career in several venues. During a stint in the Navy, he drew portraits of his fellow sailors’ girlfriends. Borrowing on the style of Alberto Vargas, he glamorized the home-town girls for a small fee, and always managed to have extra spending money.

After his discharge from the Navy, the Navajo People awarded Gorman their first scholarship to study art abroad. He spent a Bohemian year studying at Mexico City College, now known as the University of the Americas. Gorman thrived under the influence of the Mexican masters: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros, and Tamayo. He never met any of these artists, and he never studied directly with them, but their influence on his art was tremendous. Their use of color and freedom of style stimulated his imagination. Why couldn’t he apply this same freedom when depicting his own people and traditions?

During this time, the contemporary Indian art movement as we know it today was nonexistent. Indian art was confined to the “traditional” style encouraged by the Indian art schools. Gorman had no bonds to this style. He was unique. He experimented randomly.

His approach to drawing, especially, developed almost by accident during this year in Mexico. As he hurried from an oil painting class to a drawing class, he cleaned his brushes on the butcher paper on which he drew with a grease pencil. Then when he worked on the oily paper, the pencil grease partially dissolved and gave a marvelous washed effect, so he added color using turpentine as a medium. He developed and refined this technique and still uses this approach forty years later.

Gorman says he never mastered Spanish in Mexico (he actually knows more than he claims), but returned speaking broken English instead. “English is still my second language. Navajo is where it’s at.”

After Mexico, Gorman moved to San Francisco and established his first studio. He was the stereotypical struggling, if not starving, up-and-coming artist. To supplement his income, R.C. worked as an artists’ model for several university and private classes throughout the Bay area. This proved an invaluable experience in his training. While posing, he wasn’t able to participate in the classes, or receive critiques from the instructors, but he listened, observed, and absorbed the knowledge of several masters.

In San Francisco Gorman’s artistic output was prodigious. It was here that he painted the abstract canvases based on Navajo rug designs and Pueblo pottery patterns that brought him his first recognition. His career started to jell; he had more than a dozen one-man exhibitions and two-man exhibits with his father, Carl N. Gorman. He also competed successfully in Indian art competitions, bringing home first place awards in painting and drawing.

In 1967, an oil painting titled “Desert Mother” won first place at the American Indian Heritage Art Exhibition in Oklahoma City. His lithograph “Navajo Mother in Supplication” won second place. “That’s great,” he was heard to remark, “but what happened to my third entry?”

The Founding Years

In 1964, Gorman visited Taos for the first time. He roamed onto Ledoux Street and into the Manchester Gallery, which was located in the same building that houses the Navajo Gallery today. Photographs of R.C.’s work impressed the owner, John Manchester, who offered to mount a show in the gallery the following summer. The exhibit sold out, as did others in 1966 and 1967.

The Navajo Tribe observed its Centennial Year in 1968. Celebrations of the Long Walk from captivity at Bosque Redondo spotlighted the Navajo people, with special attention paid to Gorman’s art work. The only political painting of his career commemorated the Long Walk and won numerous awards (read bibliography). While preparing paintings for the Heard Museum in Scottsdale, however, he cut his right hand on a broken glass. The wound required eighteen stitches and stopped his efforts for several months, but not his expectations.

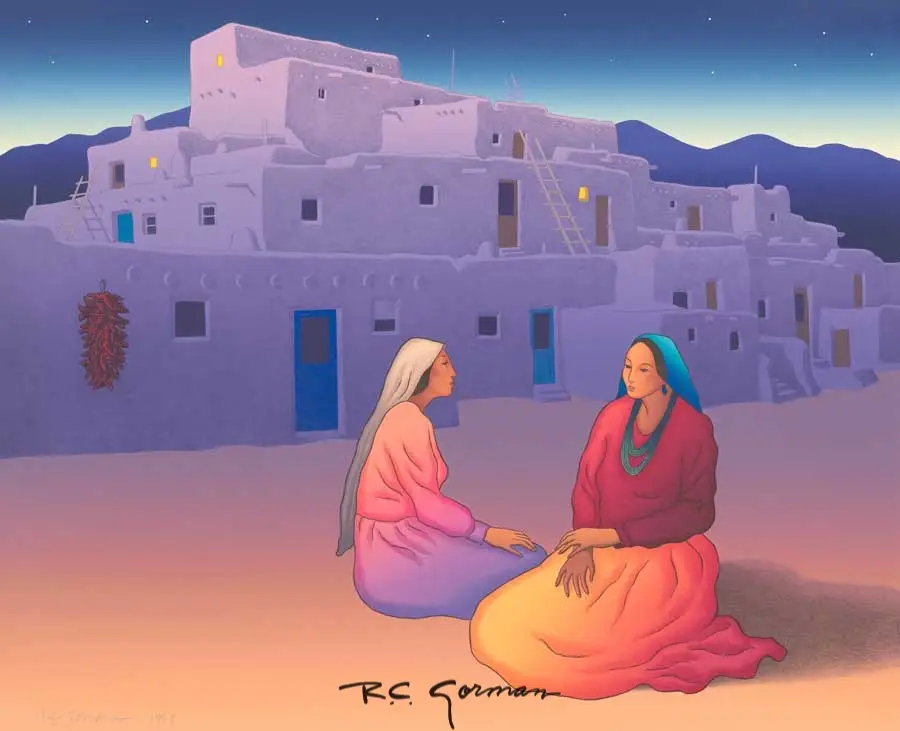

Back in Taos, Mr. Manchester had moved his gallery to the outskirts of town. His building on Ledoux Street was put on the market, and Gorman decided to buy it. Deals were drawn up, promises were made, and late in the year the historic building, parts over 200 years old, with plenty of ghosts and charm, was his. The dramatic Great Room became a perfect studio space; other rooms became the gallery and his home. Another milestone for R.C., this was the first Indian-owned fine art gallery in the United States. He named the gallery in honor of his own people and moved in. The first group exhibition was in May of 1969. The gallery roster included Patrick Swazo Hinds, Robert Draper, Al Momaday, Helen Hardin, Pablita Velarde, Charles Lovato, Cynthia Bissell, Dorothy Brett, and R.C.’s father, Carl Gorman.

Gorman shared the success of his gallery with other artists he admired. Even though the gallery building also served as his private home, every room from his dining room to his notorious nude-filled bathroom displayed art. Supporting a stable of other artists provided the challenge Gorman needed to work hard. As the gallery developed, though, most of the other artists dropped out because of lack of sales, and it became apparent that the gallery should be a showcase for Gorman alone.

Social life revolved around the gallery; Gorman enjoyed hosting parties, weddings, and all sorts of happenings during the Hippie Age. Gallery procedures were relaxed and unorthodox in those early days. Ledoux Street hadn’t been discovered yet, and gallery hours changed according to R.C.’s schedule. An imaginative approach to running an art gallery, this flexibility suited Gorman’s way and enchanted his patrons. Anyone drifting in could easily be invited to dinner, sold a painting, or be asked to step gingerly around his pet pig, iguana, or skunk.

Imagine Ledoux Street when the gallery was founded. It was a tiny, block-long, dirt path, completely residential except for the gallery and the Harwood Library. There was no street sign and no street lights. And no parking. The parking that was available was avidly guarded by the owners of the tiny houses lining the street. As it happened, Gorman’s property had only a driveway with no street rights at all.

A visitor would have to find the entrance to the driveway, walk up to the gallery window, duck under a low archway into a hidden courtyard, and find the swinging door which led, finally, to a surprisingly spacious gallery. “Where is the Navajo Gallery?” became the most-asked question of people roaming around with confusing street maps in hand.

Gorman approached this problem of “location, location, location” with characteristic humor. For some time he propped a Levy’s bread poster in the window instead of a work of art. “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s bread” proclaimed the archetypal Indian in the poster. R.C. liked the poster’s irony and kept it in his collection. It was so outrageously inappropriate that he figured people would come in just to see what the gallery was all about. It worked.

As visitors explored Gorman’s home, they often encountered him working at his easel, his model propped up, posing for his latest drawing, and entertaining him with the morning’s gossip. One reason so few studio photographs of these drawings exist is that clients bought them right off the easel. “I must always work with live models,” Gorman says. “The model sets the mood. If she’s sour, it shows. If she’s spontaneous and alive, so is my work.”

The Chaotic 70's

R.C. learned to drive in 1971 and bought an old jalopy from Rosalie Talbott, who has served as his home secretary for many years. His second vehicle was a practical van “to haul paintings around in.” That didn’t last long. Soon there was a Cadillac, followed by another Cadillac, a Lincoln Town Car, and then his succession of Mercedes. As he tried to maneuver his first Cadillac into his narrow driveway at the gallery, the passenger side experienced a mishap. Gorman ignored the damage completely, since it was on the other side and he couldn’t see it. That was his practice Cadillac. The second one missed a turn coming down the Ski Valley Road one summer day and landed in the river. Gorman escaped with an injured hand, this time his left one.

The women’s movement started in the 70’s, and ladies began using the anonymous “Ms.” title. Gorman presented the MS SIX exhibition in 1972 with his favorite women artists —another innovative concept.

1973 was an important year, with more than the usual schedule of exhibits at the gallery and elsewhere. Gorman offered Hopi artist Dan Namingha, recently discharged from the Marines, his first one-man exhibit. It was so successful that there were two more yearly exhibits before Dan moved on to a gallery in Scottsdale.

The Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe presented R.C. Gorman and Fritz Scholder in their only exhibition together. It provoked comment from all sides. Scholder: “I have tried to paint the torture that it seems to me Indians go through. Anyone who looks at the history of the American Indian realizes it has been a sad history.”

In December, Gorman presented his “Ladies of Taos” exhibit, portraits of the famous and fun ladies that had become his friends. Among them: The Honorable Dorothy Brett, Cynthia Bissell, Regina Cook, Ali Ghito, Carolyn Parr, Nula Karavas, Martha Reed, Daria Hopper (one of Dennis’s ex-wives), Jackie McCarthy, and Little Mother, R.C.’s calico cat.

Gorman’s inclusion in the show “Masterworks from the Museum of the American Indian” at the Metropolitan Museum in New York marked a 1973 milepost. He was the only living artist to be included. The Museum was so impressed with his work that they purchased both drawings from the exhibit, and the New York Times dubbed him “the Picasso of American Indian art.” So, Gorman was the first Native American to list the Metropolitan Museum in his credits.

In the following years R.C. traveled cross country to as many as a dozen one-man shows a year. Hollywood discovered Taos in general, and Gorman in particular. Jeanne Cooper, of “The Young and the Restless,” started the trek up the gallery path, followed by Gregory Peck, Martha and Hal Wallis, Lee Marvin, Senator Barry Goldwater, Ruth Warrick, George Grizzard, Linda Lavin, and, eventually, Elizabeth Taylor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Maria Shriver, Arlo Guthrie, and Danny DeVito. And on and on.

PBS filmed the first of many TV documentaries about Gorman in 1976. The six half-hour programs, collectively titled “American Indian Artists,” celebrated the Bicentennial by presenting a memorable cast: Allan Houser, Helen Hardin, Joseph Lonewolf and Grace Medicine Flower, Charles Loloma, Fritz Scholder, and Gorman. Twenty years later, friends write that they saw the series rerun in all parts of the country.

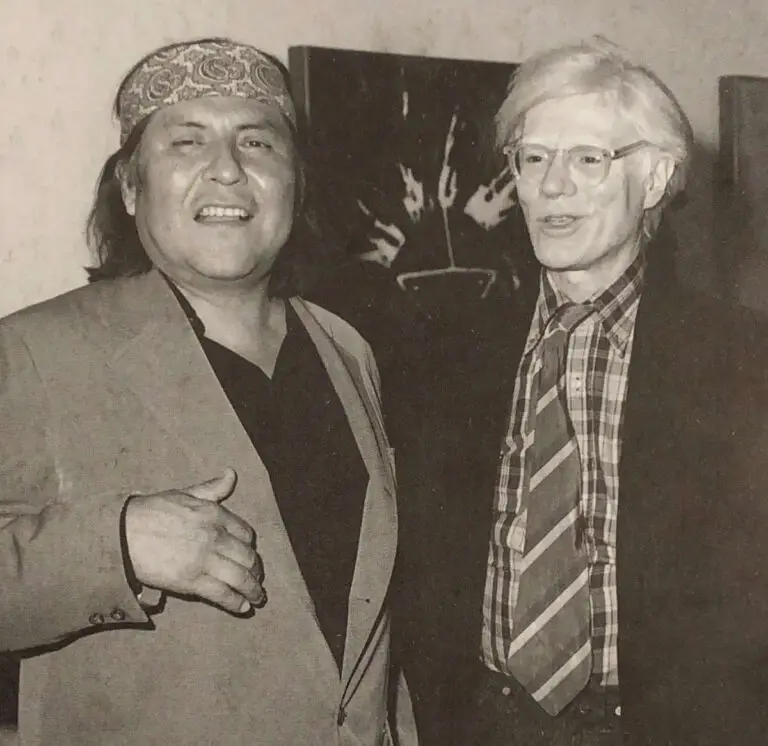

Gorman has never been avidly political, but he is an enthusiastic Democrat. In 1978, he was invited to Washington, D.C. for a dinner hosted by Vice President and Mrs. Walter Mondale in honor of the American Contemporary Artist. While dressing for the event, R.C. said he had dressed in a brother’s suit. Brooks Brothers, of course. R.C. was tickled to find himself seated at Mrs. Mondale’s right hand. Andy Warhol was seated on her left and rarely spoke. Several years later, President and Mrs. Jimmy Carter visited Taos on a skiing trip. Mrs. Carter made a point of introducing herself and her husband to R.C. during a dinner given in their honor. She was a charming fan, and Gorman sent her his NUDES AND FOODS cookbook.

As for Warhol, he and R.C. later became friends and collectors of each others’ work. Whenever Gorman visited the Big Apple, Warhol gave him the grand tour a la Studio 54 and other underbelly haunts. In 1978, they mounted a successful exhibit together in New York that was jokingly referred to as the show of “the odd couple.”

During these years, Gorman’s career as a lithographer burgeoned, as well as his first heroic efforts in bronze. He experimented in paper casts, ceramics, silkscreens, and even tapestries. The gallery became more and more viable, and the resulting responsibilities kept Gorman on the fast track.

January 8, 1979, was dedicated as “R.C. Gorman Day” in Taos. He was roasted, toasted, and given cheerful recognition by his fellow Taoseños. During the final toast, however, Mayor Phil Lovato remarked: “R.C. Gorman is an example of a spirit of Taos which attracts artists. There seems to be something about Taos that for many years has attracted the arts and inspired artists. We have before us a living example—the man we honor today.”

A Home Where Art Can Run Amuck

Gorman’s home on Ledoux Street was perfect for the gallery, but it was getting crowded. He needed more room, more privacy, and space for his personal art collection. Again he bought another old adobe fixer-upper, which had originally been a sheepherder’s cabin, so he felt right at home.

Casa Gorman, situated just north of Taos with a liberating view of Taos Mountain, needed a lot of work. Gorman wasted no time creating a ballroom-sized studio, an Olympic-length swimming pool, a guest house, a new kitchen, a library, a wider living room, and a Japanese style sculpture garden. The only rooms left of the original house were R.C.’s bedroom and a jacuzzi room built by hippies two owners back. He suffered from the same building fever as the Medici Popes.

All this activity resulted in a stunning home that only Gorman could have conceived. It inspired him to start collecting art seriously—Miros, kachinas, a few Picassos and Chagalls, and elephants from India. He supported promising young artists, or the latest kitsch, whatever caught his eye. And art was placed everywhere. The model’s dressing room had no mirror so there was more room for pictures. One fine day R.C. bought a concert grand Steinway in the morning and a new Mercedes in the afternoon. After his years of work, this kind of cheerful extravagance was fun.

The work continued, of course, and Gorman was more productive than ever. The grueling travel schedule exhausted everyone, except Gorman, who flourished. Trips to Japan resulted in a collection of woodblocks which are treasured by collectors as small, perfect jewels. His increasingly numerous tours of Europe always coincided with exhibitions and printing projects in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. His international clientele increased with each appearance. Charm, humor, and art speak the same language.

During the 80’s the large format books on Gorman’s art started rolling off the presses of national publishers. Each book played a part in educating a wide audience in Gorman’s background, his family, and his flamboyant personality. The universality of his art grew stronger. His new home brought out Gorman’s hospitality; yet another First Lady came for a private visit. This time it was Jacqueline Kennedy. She was gracious and generous of spirit, and those who met her that quiet day will never forget her. Her poise and gentle demeanor impressed Gorman as well.

The hectic pace of the 80’s finally felled Gorman in 1985. His gallbladder became infected, it burst, and required major surgery and several months’ recovery. He kept his wit intact through the ordeal, always eager to give advice to friends experiencing the same problem. “It’s really awful,” he assured them. “Worse than giving birth or having heart surgery.” Not that he would know.

The next year, fully recuperated, Gorman tackled a full schedule of exhibitions. Returning home from Europe in the spring, he visited Cambridge to receive Harvard University’s Humanitarian Award. This prompted him to endow an annual scholarship for Taos High School students of Indian and Hispanic descent. On the other coast, Mayor Dianne Feinstein dedicated another R.C. Gorman Day in San Francisco.

In 1986 Gorman decided that the Navajo Gallery would host his annual Indian Market Exhibition in Taos, instead of in a Santa Fe gallery. It is now an annual event, scheduled for the Thursday before the actual market starts on Friday in Santa Fe. Other Taos galleries followed his lead, and now a full docket of shows opens on that day. Traffic jams on the road between Santa Fe and Taos that afternoon present a real problem, but most of the visitors return to Santa Fe pleased with their new Gorman drawing, litho, bronze, book, or poster.

Is Imitation the Finest Form of Flattery?

There have always been artists who use Gorman’s style for their inspiration. In other words, they’ve copied him to one degree or another, though they sign their own names. In 1987, however, there appeared a scattering of very inexpensive “Gorman originals.” R.C. was sent photos of these drawings for appraisal, and it became clear that they weren’t his. They were copies done by a clever lady forger who specialized in Gorman, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Agnes Martin. She also practiced medicine without a license and was living in the United States without permission of the Swiss or U.S. governments.

R.C. has always admired strong-willed women and finds the lady’s saga continuously entertaining. Is she still in jail for the O’Keeffe caper? Has she been deported again? Does she claim a law degree now, or has she gone back to photography? She has a website where you can keep up with her, but I can’t reveal her name because she claims innocence. Maybe you could punch in “forger.com” and see what happens. Moral: If someone offers you a Gorman drawing for much too low a price, look at it very carefully.

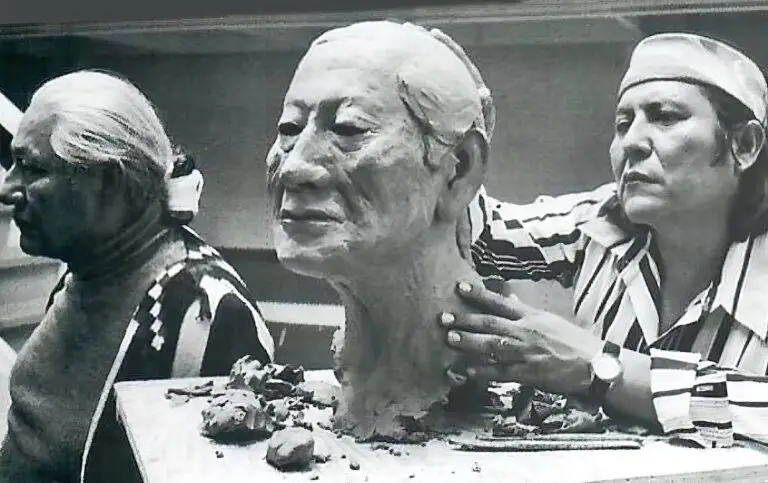

Gorman executed his first bronzes in San Francisco in the spacious studios of Editions Press. When that concern fell victim to the gamble of speculators, R.C. decided to produce the bronzes himself, using the Shidoni Foundries outside of Santa Fe. He sculpted the clay models in his Taos studios, then hauled them down to Shidoni where expert artisans supervised the castings. R.C. checked on the progress of each sculpture with a quick side-trip on his way to lunch in Santa Fe. This successful collaboration produced eleven bronzes in as many years.

In 1995, Gorman dedicated a heroic bronze portrait of his father in honor of the Navajo Code Talkers. Carl Gorman was the oldest of the original twenty-nine Navajos who volunteered to form a secret division of the Marine Corps. They coded the Navajo language among themselves and were scattered across the Pacific during World War II. It was dangerous duty, but the Japanese never broke the code.

Most Americans had never heard of the Code Talkers. Only in recent years has their story been told and have they received recognition. It was a poignant ceremony, then, when this bronze was dedicated on Veteran’s Day and donated to the campus of R.C.’s alma mater, Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. The Gorman family, several dozen of the remaining Code Talkers, appropriate dignitaries, and hundreds of Native American students attended the ceremony. The bronze remains on the campus as a tribute to the men who served so honorably and as a monument for the younger generations’ aspirations.

When R.C. was asked about what the Code Talkers and their service to the country meant to him, he said: “You need to talk to my father and the rest of the men. They were there. They served. I was not there.”

Believe it or not, the bronze has caused some controversy. But nothing compared to the uproar stirred up when Gorman attended a luncheon for the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World. The guest of honor was a descendant of Columbus, the Duke of Veragua, and Native American protesters were clustered around the entrance, banners waving. They were angered to see R.C. there, looking as one wag said “like a Cartier yard sale.”

He was dressed in lots of gold—rings, bracelets, any gold he could find. He told the Duke, “The Spanish came here for this,” pointing to his tinsel. “So, I’m bringing it to you.” The Duke laughed and tensions settled down.

Knee surgeries and a knee replacement have slowed R.C. a little. Even though he’s recovered completely and sticks to a strict exercise regime, he has little inclination to race around to the almost monthly exhibits as he did previously.

His 1998 schedule included exhibits at the Adagio Gallery in Palm Springs, the East-West Center in Honolulu, and the Four Winds Gallery in Australia. Then a European tour with his sister, Donna, and work on a lithograph at the Lithografia R. Bulla press in Rome. In August the Navajo Gallery celebrates the Thirtieth Year Anniversary Celebration. After that, he’s off again.

Does R.C. have plans for the future? Of course he does, but he says: “I don’t plan things. If you plan too much and it doesn’t work, you can be disappointed. So I don’t worry about the future. It always seems to get here… but there’s no retirement in sight so far.”

Ms. Dooley wrote this essay as part of the book, The Taos Diaries 1968-1998, which commemorated R.C.’s 30th anniversary in Taos. Virginia Dooley directed Navajo Gallery activities until 2007. She died in Taos in April 2008.